The Oxford German Network is delighted to announce the launch of a new essay competition for 16-18 year olds in the UK: ‘A German Classic’. The piece of classic German literature celebrated this year is Goethe’s Faust, Part I. To find out all about entering the competition, visit the OGN website here, where you’ll also be able to download a wealth of podcasts and other study resources to help you. The competition prize has been generously donated by Jonathan Gaisman, QC, whose first encounters with German as a schoolboy left him with a lifelong enthusiasm for German literature. In this week’s blog, he tells us how this passion came about.

My first German teacher, a perceptive man called Roy Giles, wrote in my initial term’s report: “He will do well at this language, because he likes the noise it makes.” And so I did: aged just 14, I was immediately delighted by the disembodied voice on the audio-visual tape, which was how my acquaintance with the German language began: “Hören Sie zu, ohne zu wiederholen”. The cadences of this unremarkable sentence, bidding one to listen without repeating, still enchant me today. The story on the tape told of the prosaic doings of a German businessman attending an industrial fair. He was called Herr Köhler. Presumably this was a joke, though one unlikely to appeal much to schoolboys. But what caught my attention was the dramatic plosive – unlike anything in English – available to those willing to launch into the sentence “Plötzlich klingelt das Telefon”. That this sentence, like its companions, was of an almost Ionescan banality deprives it of none of its nostalgic appeal: I was already reaching for the handle of the door.

Four years later, by the time I left school, I had passed well and truly through. In those days, studying a modern language involved intensive study of literature. We studied Prinz Friedrich von Homburg and other writings of Kleist, carefully read Maria Stuart, and more than dabbled in the shallows of Faust part I. A personal enthusiasm bordering on obsession led me to commit large slabs of Faust to memory, and they are still there. Giles had introduced us to recordings of Gründgens‘ performance of Mephistopheles in Faust; another teacher, Mark Phillips, earned my particular gratitude by playing me Schubert’s Die schöne Müllerin. And so the way was opened though literature to poetry, to Lieder, to Wagner and to the extraordinary contribution of the German language to the life of the arts from the 18th century on.

German literature and culture had thus passed into my bloodstream, and become part of my imagination and mental being. So it was inevitable that I would take modern languages to university, where I was lucky enough to be tutored by a third fine teacher, Francis Lamport, at Worcester College, Oxford. Sadly, before long, but not before adding authors such as Büchner, Grillparzer, Kafka and Mann to my acquaintance, I abandoned the outer form of German studies, and dwindled into a lawyer. But the fire within was alight, and it burns still. The few years between the ages of 14 and 18 when I studied German represent the dominant intellectual influence in my education, and the one for which I am most grateful.

The simple aim of this prize is to enable other students to set out on the same journey which has enriched my way of seeing the world, to discover the inspiration of the German literary canon, and to avow the great truth uttered by Karl der Groβe himself: “The man who has another language has another soul”.

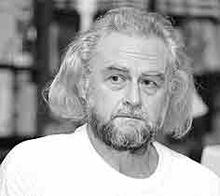

Jonathan Gaisman QC