Every so often, we at OGN Towers like to take a look round the blog-o-sphere and see what other people are writing about German-language life and culture. Last week we reblogged a post by Mary Boyle about her stopover in Aachen. This week, we spotted Heike Krüsemann’s recent review of Wolfgang Herrndorf’s acclaimed novel, Sand (2011). Heike published her post on her blog here: From the Sea to the Night – but mainly in the Desert. Review of Sand by Wolfgang Herrndorf. She’s also written for the OGN blog in the past. But now, read on…

[An edited version of this post was published under #RivetingReviews on the European Literature Network website, 12 April 2017. ]

North Africa, 1972. A man with no memory wakes up in the desert with a massive hole in the head. So far, so yawn: please, not another one of those lost memory characters stumbling around the plot trying to solve a mystery slash crime, been there, done that, keep your T-Shirt. Not so fast! Carl (named so after the label in his suit) is not your average unreliable narrator. In fact, although we’re trapped inside his head most of the time, he’s not the narrator at all. Somewhere, someone’s sitting at a desk writing all this down in the first person, someone who was there as a seven-year-old, dressed in “a T-shirt with Olympic rings and short lederhosen with red heart-shaped pockets”. Who’s he? Not sure – everyone in Sand is reliably unreliable, apart from the author himself, who’s reliably, erm, dead.

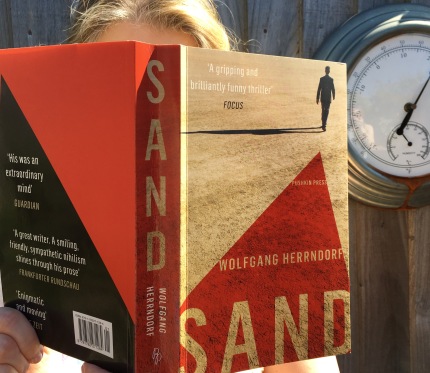

After being diagnosed with an incurable brain tumour in 2010, Herrndorf churned out some literary gems – including international bestseller Tschick (English title: Why We Took the Car) and Sand – and then, in 2013, shot himself. Perhaps fittingly, Sand is stuffed full of pain, gallows humour, false hopes, dead ends, absurd coincidences, misunderstandings, senseless chance events, torture, and death. It’s set under a desert sun so merciless, that a mere glance at the cover triggers an inverse Pavlov’s dog reaction of dry mouth for the reader. Sounds offputtingly soul-crushing? Not so! What’s holding it all together, over 68 chapters and five books from the Sea to the Desert, the Mountains to the Oasis and on to the Night, is the search for meaning, never mind the answers, it’s the questions that matter. Of those, there are many – and it makes for a hilarious, intriguing, heart-breaking, and ultimately gratifying read.

‘And now Lundgren had a problem. Lundgren was dead.’

A young simpleton murders four Hippies in a commune (it is the 70s…), a mediocre spy doesn’t survive a handover, a pair of bumbling policemen investigate – to not much avail, what else – a dangerously smart American beauty muscles in on the act, a fake psychiatrist tries to get to the bottom of Carl’s subconscious, a small-town crook and his henchmen get involved in the odd bit of kidnap, torture and blackmail. The hunt is on for a man called Cetrois, who may or may not exist, and a mysterious centrifuge makes an appearance, or it might be an espresso machine, who knows. More important seems to be a mine – this could mean a number of things, a bomb, a pit, a cartridge for a pen, … a cartridge for a pen?!

Yes – now let’s talk language, and translation. The characters in Sand are supposed to be speaking French, and thanks to Pushkin Press and translator Tim Mohr, we can now read it in English. Think ‘Allo ‘Allo. Tim Mohr, writer, translator, former Berlin Club DJ, and lucky owner of the coolest mini-bio ever, constructs an achingly immediate desert world by locating the English prose somewhere between 70s nostalgia and the contemporary. In German and French, ‘mine’ can mean the inside of a pen, and Carl’s knowledge of this means that he’s a step closer to solving the puzzle, but is it close enough to see it through? You decide for yourself, but really, that’s not the point. He tried, he really did. And in the end, that’s what matters.

Sand

written by Wolfgang Herrndorf (Rowohlt Verlag, 2011)

translated from German by Tim Mohr

published by Pushkin Press (2017)

Heike Krüsemann is currently completing her PhD thesis on representations of Germanness in UK discourses. Her Quirky Guide to Oxford will be published by Marco Polo in German and English in 2018.

Heike’s 30 second video review of Wolfgang Herrndorf’s Tschick

Heike’s blog German in the UK

Twitter: @HeikeKruesemann